How Japanese Manufacturers Lost Their Way

This was originally written in 2003

In describing American car buying tendencies, it has been said: “As long as it’s American, the size of a Scharnhorst, and boasts electric cup holders and the right badge on the front, they’ll buy it.”

Biting language. No surprise, then, that this comment comes from a Brit. Anthony ffrench-Constant is an editor at the UK-based CAR magazine, a publication with perhaps the right amount of distance from the United States to see us clearly, but possibly suffering too large a communication gap to completely assess our values.

The Scharnhorst, Google tells me, was a German battleship from World War II. Oh, I get it. We like big-huge cars, big-huge SUVs, and big-huge torque. We want big-huge marketing promoting a product with a big-huge heritage. Godzilla footprints across our cultural landscape, crashing stomps of ads and tunes, images and personalities pitching us larger-than-life products that are bigger and better, new and improved, one size fits all. He could be right.

ffrench-Constant (yep, two fs, both lower-case) is very well-issued in his perspectives. Though all writers are subject to the flying pen, where your words get away from you, courtesy of their own strength, and end up creating hyperbole, here he is actually treading on very sturdy ground, ice thick enough so that it doesn’t matter that it is ice at all. We do love brand.

Ford. Budweiser. Nike. Coke. Kraft. Hilfiger. Bose. NASCAR. If you’ve seen Fight Club you may recall Edward Norton’s misguided longing for material items. The right furniture. The right clothes. That set of pots and pans that would complete him the way a soul mate–or Jesus–might. We certainly can be obsessed, as a country, over material things, marketing, and status. Here, Wal-Mart is king, McDonald’s is queen, and gluttony is convention. For a large portion of this country, then, ffrench-Constant is dead-on.

Statistically speaking, most people in the US couldn’t give a hoot about a sports car. Too small, too stiff, too expensive, too much to insure. I have even heard a friend of mine, who is exactly 25 years old, consider out loud that the VR6 Volkswagen Jetta may not be a good choice for him because of ‘poor gas mileage.’ He was “thinking Turbo Diesel (TDI)”. Now I may be getting on in years myself, but the first time I consider gas mileage as the single, major factor in an automotive purchasing decision, it may be time for a prostate massage and a bus pass. Obviously, what we have here is a failure to communicate.

ffrench-Constant says that J Mays, the new Vice-President of Design charged with shaping a new Ford, told him: “American isn’t interested in design.” Consider now that this isn’t some bitter journalist scribbling out banter –this is a powerful declaration by a person of considerable accomplishment, supported by years and experience.

Mays may not have intended to issue a blanket mission statement, but he didn’t just pull it out of the blue. His statement actually works when one considers that automobiles are a business, and business is all about numbers. As I thought it, though, sports cars were not. I have lived under the impression that sports cars were about exciting ideas and new thinking; the power of suggestion; power to weight ratios, balance, and colors; turning heads and forcing smiles –even giggles for a very good sports car. Numbers crunching, as I had it, applied more to the Toyota Camry than the Supra, but for many manufacturers, especially Nissan, the days of the unprofitable, emotional sports car are over –for now anyway. Pity us.

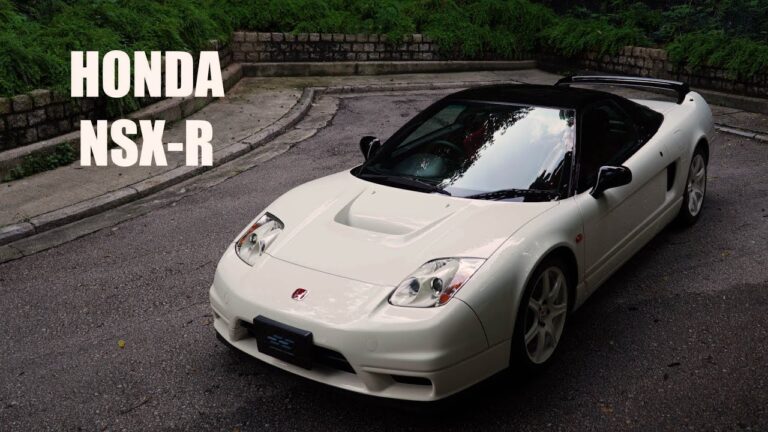

It shouldn’t be surprising then to see the market-shaped sports car to be full of compromises. Shipped over to make money, not legends, the new-age sports cars are often hindered more by compromise than their previously most significant nemesis, emissions. This is not to say that pure visions-on-wheels no longer exist, as they certainly do. 911s, NSXs, and even, to an extent, Miatas, are all at least 150 proof. But the more I look at this ‘evolution’ of the sports car, where parts-bins are not just free game, but the foundation; platform sharing is not just a necessary evil, but the standard. Different is expensive. Still, this seems to be something quite different, and considerably more dreadful than simple economics: the ‘Americanizing’ of the foreign automobile, especially the Japanese automobile.

At some point, in the eyes of the manufacturers, it stopped being cool to be yourself, possibly right around the time said manufacturers became so staggering successful that they realized that they had something to lose, and possibly more to gain by going more mainstream. For all of its stunning, dramatic failure in the mid-90s, it could be that the formula for the Japanese, technologically driven sports car was dead-on and simply had a few misapplications market-wise; for whatever reason, they eventually went left or short of their target. This is, admittedly, only a guess, and if you ask product planners for leading manufacturers, not one worth wagering millions on, so here we are. Innovative becomes quirky, original becomes risky.

As I recall, what got the Japanese carmakers to this point was doing it their own way. There once was–for an uncomfortable length of time, anyway–a disparity of quality and character that made Japanese cars so desirable. While the Big 3 here struggled mixing emissions and emotions in the 1970s and 80s, Japan lobbed another idea over the fence: technology. No heaving V8s breathing twice through a black-rubber labyrinth of vacuum hoses, but a different approach. Advanced cylinder heads sat atop 4 pot blocks, spinning as high as they needed to, making as much power as the chassis required. Less displacement. Less emission. Less is more. Rather than weezing hulks walking our highways and wilting our flowers, we now had a choice. This was new thinking. The 80s made the market for Japanese cars in the US what it is today. The United States, or the part of it that evolves, embraced the Japanese car for its thinking, design, and durability.

Fast forward two decades and we seem to be at a less significant place. Japanese car makers are preoccupied with giving their cars “more”: more torque, more luxury, more models, more red, white and blue; American car makers are flies on the wall of Toyota board meetings wondering how they do it, ironically trying to make their cars more Japanese, more European –and somehow we all are left with less. Why?

The answer is more elusive and complicated than we can address in one sitting, but a troubling, visible contributor I see daily is mainstream automotive media. I read pretty much all of the major automotive writing produced –magazines and books, newsletters and websites, message boards and such. This media, compiled rantings, ratings and reviews, has an authority to its voice when it speaks in unison. Dangerous potential.

When Japan ships over their newest creation to be driven, tested, and explored, I cringe to see it being done so by journalists who cut their teeth on Corvettes, cubic inches, and leaf springs. As eloquent and influential industry commentators, their opinions are significant and their effect should not be underestimated. Tip-toeing carefully, I would go as far as to say that big-time media would take a V-8 over almost anything, “Torque as flat as Kansas.”

Oh, joy.

In the Road & Track Road Test Annual 2002 Senior Editor Andrew Bornhop, in choosing a BMW M Roadster over a Mercedes SLK32, explains himself: “Why the (BMW) over the (Mercedes)? Simple. It has a manual gearbox, and it doesn’t rely on a supercharger for power.” I’m still reeling over that windfall of logic and will let you know when I stop.

For all of their necessary open-mindedness, they seemingly can be diverted and amused by the Mini Coopers of the world, and of course are baited by the big power of the Altima, but it seems like they are allowing for such entertainment rather than being moved by it. They view peaky, technologically-advanced sports cars with the same gentle amusement people without children have for those that do. Nice for someone, but not in my garage. We badly need equal representation.

The depth of this juxtaposition came wallowing home and sat on my lap when Douglas Kott asked for more torque out of the Honda S2000s F20C powerplant. In a roadster showdown (Road & Track Special Series: 2001 Sports & GT cars) involving the Audi TT, BMW Z3, and Porsche Boxster S, Kott committed the heresy. “Please, Honda” he begged, “Make it 2.5 liters and give me 30 lb.-ft. more torque down low; I’ll gladly accept a 7500 RPM redline.” Wars have been started over less. Honda, conductor of 19,000 RPM Formula 1 orchestras, deity of everything under the valve cover, forced to sit and listen to this insipid American whining? Anyone that steps out of a S2000 and wants more torque and less revs missed the whole first half of the movie.

Fast forward 2 years, and take a gander at the checklist of revisions for the 2004 Honda S2000. Kott, your wish is granted. Increased displacement at 2.2 liters. Redline lowered a full thousand RPM, now at 8000. More torque, less revs. The irony here is that 99% of this post was written years ago, months ago before Honda announced any changes to the S2000. Unfortunate prescience.

How about an example closer to home? Peruse Nissan’s 2004 line-up, and tell me it doesn’t smell like apple pie. Bigger displacement V-6 engines, big 4s stuffed into small cars, no roadsters, and no forced induction as far as the eye can see, SUVs and big trucks leading the charge. Nissan and Honda have some genuinely progressive styling and engineering poured into their current line-up, but it is all done so with American style, to American liking, Americanized.

Shouldn’t that be their aim, you ask –to give us what ‘we’ want? It is my belief that those of us observant enough to look at the badge on the hood before we climb in; that buy, not lease; that push the car with any vigor or treat it with any respect, care very much what we’re driving, and about all of its qualities. We not only want design, we demand it.

Quality is a prerequisite –searing engineering par for the course. While the larger, bi-polar crowds are being chased by sweating study groups and Tums-chewing market researchers, there are those of us that sit quietly, a silent minority, waiting for common sense to come back around; for the crowds to settle a bit and rejoin logic. Thought bubbles over our heads might say ‘Engineering,’ ‘Character,’ ‘Value,’ ‘Performance,’ and “Don’t make us share our legendary Z car’s engine with our mom’s Infiniti.”

Making cars is admittedly a big investment with a big risk, so study away. It bothers me though to see Japanese cars lose their identity, melting into something as American as grilled cheese. This castigation of Japanese craftsmanship is not new, but for some reason, possibly mainstream automotive media, now the Japanese are listening.

Note to Japan: Appeal to the masses with your mass-appeal models if you must, but be careful with your sports cars –don’t lose sight of what got you here. And if you’d like to avoid competition, consider this in regards to this newfound market you’re easing into: nobody does boring, sleepy mediocrity like the Big 3.

Careful, now.