As I Get Older, My Taste In Cars Is Changing

This post was originally written in 2005

Maybe I’m just getting old.

As that becomes true, it’s funny how often that theory holds water. Everything just looks and feels different. Four-door cars are a good thing, going to the grocery–for hours–is fun, and boredom is an entirely fortuitous condition not to be bothered by time nor task. I had it backwards all along.

In lockstep with slight changes in my musical taste (I suddenly have some) and peculiar seasonal affections, certain nameplates and models begin to look, somehow, different. Bob Dylan’s tortured grunting was quite clearly genius too opaque for me to gather in at 16, so I listened to something else until my ears ripened. Now he rocks. Same with Vidalia onions, naps, and weddings.

Automotive brand and product also has suffered from my skewed, wiser perspective. I like stuff I didn’t used to. Take, for instance, American cars.

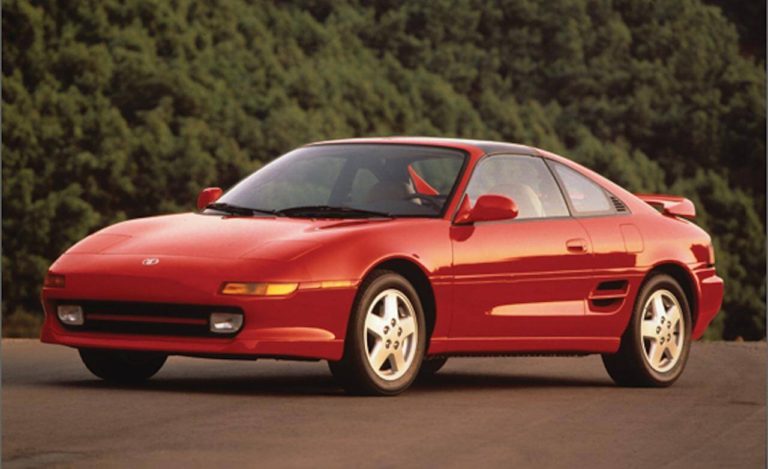

Save the hate mail, I grew up on lots of noise and cubic inches, my first car being a loud, header’d Chevy, so I’m no brand snob. I’ve always stared a little longer at Ford Mustang Cobras, SVT Contours and Lightnings; Buick Grand Nationals; Chevrolet Corvette ZR-1s; Pontiac WS-6 Trans-Ams and other fast F-Bodies. For the most part, my affinity and disdain are applied equally across the globe. I simply like cars that reflect engineering effort. Renault Clio Williams, Integra Type R, BMW M3 Lightweight, Lotus Elise, Acura NSX, Toyota Supra and MR2, Mazda RX-7 and Miata, Corvette Z06. Performance applications of everyday vehicles should reflect a genuine intent to enhance the car, overall; this includes performance, personality, lap times, and styling. Stuffing a bigger engine under the hood will indeed make a car faster, and many times is enough to get the job done, but its usually not that simple. Your average V-6 minivan will accelerate faster than my 1985 Toyota MR2 at home, but what about handling? Braking? Balance? Road feel?

Soul.

Which brings us to why, in spite of a handful of exceptions, American cars have been known to, well, suck for quite a while now, bland at absolute best. Take muscle cars for example. In the 50s and 60s, from Cadillac to Studebaker, Oldsmobile to Ford, American cars had more soul than James Brown. They were chromed, loud, and pissed off, many of them socially irresponsible and borderline illegal from the factory. Hidden in VINs and under barn-door hoods were big engines with bigger displacement, special packages available to savvy buyers through the simple check of a box. Six-packs, Hemis, Dual-pointed ignitions, tunnel-rams, trunks, tigers, and an endless combination of cranks and blocks yielded whatever displacement and ensuing horsepower the application called for for surprisingly little cost, much to the angst of the mid-century automobile insurance industry. And that is not to say that performance alone dictates quality. Though that Woodward-Ave world was one far less connected, and thus less global, than the one we suffer from today, America was very much a source of styling inspiration and luxury know-how for the world to mimic as well. At one point, Cadillac was called “The Standard of the World.”

Of course these were cars being delivered to a largely open-minded public ignorant of the pending gas crisis in 1973. After that brilliant run, the American automotive landscape would never really be the same, soon to face competition arriving on big, huge boats from the strange island of Japan. Since then, confidence scattered, American car manufacturers have always struggled with how to react to the nature of the Japanese car. I would guess their initial reaction might’ve been gentle amusement, this new stubborn child wrapped firmly around one leg like a Koala bear, but this has obviously changed. Bob Lutz is sending out Pontiac’s Solstice a full 16 years after the Miata got the gig. In sports-speak, this is called “playing from behind.”

Certainly recent shifts in product have ironically brought the previously divergent brands closer together, the backwards Americanizing of the Japanese car, but we’ve hummed that tune before. What about America as an automobile-producing nation–where is the energy coming from? Not surprisingly, the past.

When Ford set out to design a GT for the new millennium, they squinted a little and traced the old GT40. Time for a new Mustang? See 1967. Same with the Dodge Charger, Chevrolet SSR and, to an extent, the Chrysler 300C and PT Cruiser. And for the most part, they’re all fantastic automobiles. As a nation, we’ve never lacked the ability, but possibly only the timber legs to stand on and shout out about it. So here we are, model year 2006 upon us, and I find myself actually curious what Detroit will issue next. I am sincerely disappointed that Dodge does not offer the Charger with a manual gearbox, more than a little curious about what SVT will do with the next Ford Mustang, and looking for people to recommend the Dodge SRT-4 ACR to (no one in my inner circle, mind you–I’ve still got principles). Detroit and its product, rather than its dramatic demise, are the issue. Have I changed, or have the cars?

Growing up, I was introduced to all of this mess by my father. You might hear me mention him a lot, he having literally delivered the automotive world into my lap at an age where I could appreciate its playfulness and dreaming accessibility. In this toy chest, he handed me everything cars: burnouts, technical explanations of flywheels and cams, 60′ times, and appreciation for value, among 11,000 other playthings crammed inside. (I actually just got off the phone with him; he caught a recent episode of Top Gear and was intrigued by the Mazda RX-8. I’ve never heard my father say ‘9000 RPM’ in my life, but he just did, twice). I’ve noticed the crow’s feet crowd up around his eyes through the years, behind them decades of experience watching the automotive industry ebb and flow. There is no future the past hasn’t already seen.

Fully aware of the dangerous potential summoned by authentic wisdom, I carry on walking about the magical automotive landscape maybe just a little bit slower, less in a hurry, intrigued by this new haze everything has–considerable, but no longer opaque.